Introduction

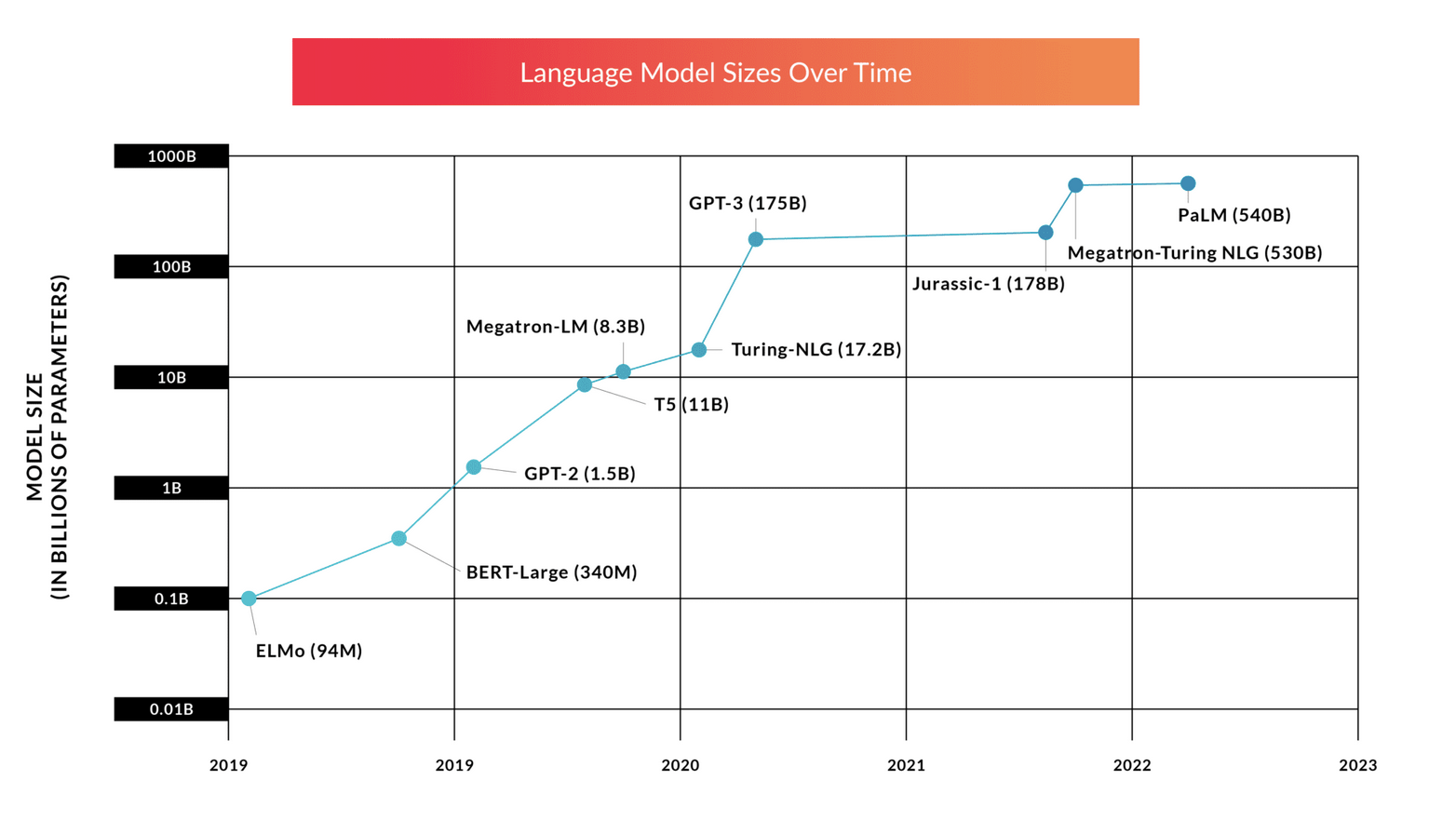

In recent years the world of AI has turned into a race for bigger and bigger models. These models are amazingly powerful and adapt to so many cases. However these generally trained models, also known as foundation models are not always good enough for businesses use cases. Users want specialisation, specific adaption to their unique use cases, with their unique data.

Off the Shelf Models Can Only Go So Far

So what can we do ? Naively, we can do nothing, i.e zero shot, we prompt and hope for the best. Alternatively we can do some few short learning, we stuff a few examples of expected inputs and outputs into the prompt and hope the model will learn well enough. this approach is known as Prompt Engineering. This is a nice approach due to it’s simplicity, however, with limited context windows we quickly run into a wall with how many examples and corner cases we can fit into the prompts.

Classify the text into neutral, negative or positive.

Text: I think the vacation is okay.

Sentiment: neutral

Enter Model Tuning & Parameter Efficient Fine Tuning

Ok, so we looked at our easy options, and while accessible just aren’t good enough for many use cases. That traditionally left us with model fine-tuning / retraining. Modern models are massive, with billions of parameters to update, the cost and technical expertise required to carry out such an endeavour is prohibitive for many players. A new way was needed to update models with all of our training data, but without having to update billions and billions of parameters.

As these models grew and traditional fine tuning became unwieldy, we’ve seen a large number of solutions being prosed to combat the issue. These solutions aim to tune only a fraction of the original models parameter count. These methods have collectively become known as Parameter Efficient Fine Tuning of PEFT for short.

To quote Andrej Karpathy:

PEFT (Parameter Efficient Finetuning, LoRA included) are emerging techniques that make it very cheap to finetune LLMs because most of the parameters can be kept frozen and in very low precision during training. The cost of pretraining and finetuning decouple.

Making Sense of the PEFT landscape

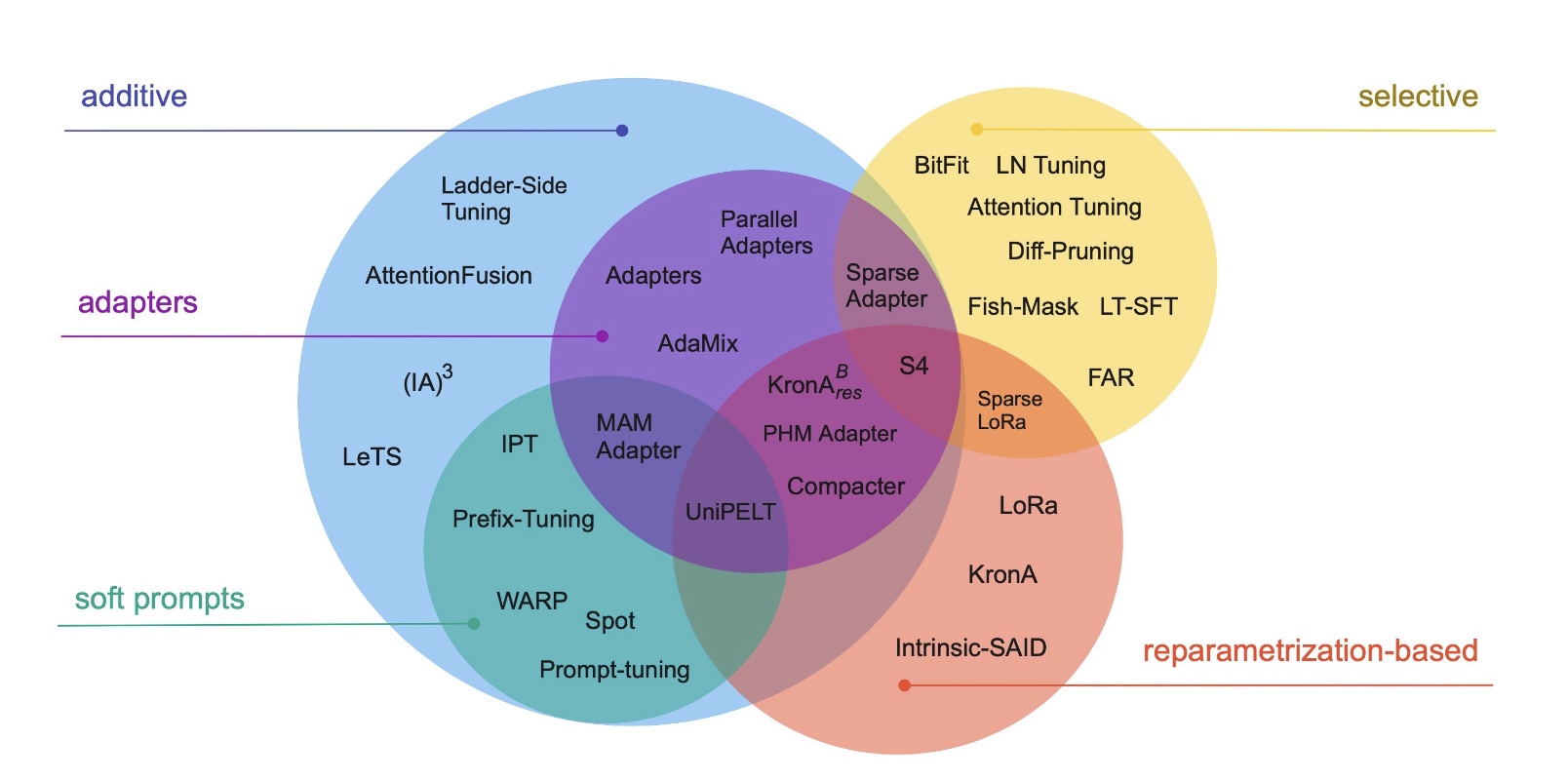

In this great overview paper, Scaling Down to Scale Up: A Guide to Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning, the authors make the first attempt to provide some taxonomy of the different approaches we have available.

Mainly we have 3 approaches (with some overlap):

- Additive: Involves introducing additional parameters or modifications to the model architecture to enhance its performance, often by adding new layers or connections.

- Selective: Focuses on selectively updating certain parameters or components of the language model to improve specific aspects of its output, such as fine-tuning only certain layers.

- Reparameterization: These techniques exploit low-rank representations to diminish the quantity of trainable parameters. It’s now a well studied fact that neural networks have low rank representations.

Comparing & Choosing

Given the large amount of possible options, we may feel overwhelmed about which approach is right for us. Luckily the paper also provides us with a framework to compare and evaluate different PEFT approaches. So when we are choosing which method to use for our specific use case we must take into account 5 key characteristics:

- Storage Efficiency - Will it increase the model size ?

- Memory Efficiency - Will it increase the memory footprint during training & inference ?

- Computation Efficiency - How much does it change back-propagation costs ?

- Accuracy - Will it lead to better outputs for my use case ?

- Inference Overhead - Will it add latency during inference ?

An example of how additive models can help with Memory Efficiency

In practice, depending on the setup, training a model requires 12-20 times more GPU memory than the model weights. By saving memory on optimizer states, gradients, and allowing frozen model parameters to be quantized (Dettmers et al., 2022), additive PEFT methods enable the fine-tuning of much larger networks or the use of larger micro-batch sizes

Now that we have some idea of how to evaluate these approaches, let’s take an illustrative example for each class of PEFT technique.

A Closer Look At Specific Approaches

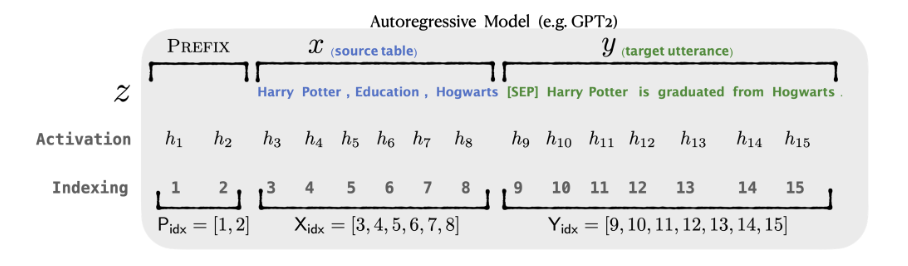

Prefix Tuning (Additive)

Original Paper: Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation

Prefix tuning can be thought of as type of prompt tuning, but instead of using text, we use completely tuneable vectors, who’s job is to give task specific context for the input tokens that will follow. What do I mean by task specific context ? Well for example, we might want our network to get better at translation, sentiment analysis, summarisation etc.. Intuitively these prepended tune-able tokens are trained to give the following tokens some awareness/context of the task they are expected to perform.

From the paper itself…

Prefix-tuning prepends a sequence of continuous task-specific vectors to the input, which we call a prefix, … . For subsequent tokens, the Transformer can attend to the prefix as if it were a sequence of “virtual tokens”, but unlike prompting, the prefix consists entirely of free parameters which do not correspond to real tokens.

The number of free parameter tokens we can prepend to the input can range of from 10 - 200 extra tokens. Prefix tuning is incredibly parameter efficient, but appending more tokens adds more computational complexity due to the transformers quadratic complexity, which will add overhead at inference time.

BitFit (Selective)

Original Paper: BitFit: Simple Parameter-efficient Fine-tuning for Transformer-based Masked Language-models

Here we are only going to tune a small subset of the existing network weights with no modifications to the overall network. In this particular approach we only fine tune the biases of the network which make up roughly ~0.05% of the total model parameters.

This method is great as it vastly reduces training times while not impacting the models efficiency in terms of memory, compute or inference latency. However it has been shown that this approach works best on smaller models of < 1B parameters, and didn’t perform as well as other techniques at larger sizes (GPT3 scale).

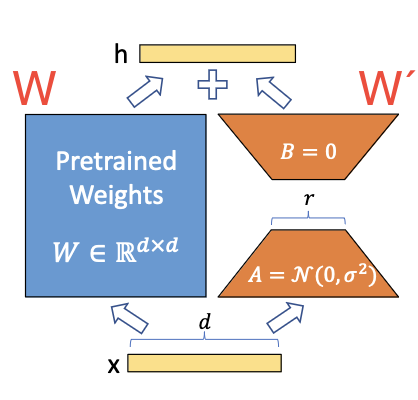

LoRa (Reparameterization)

Original Paper: LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models

So the insight for this technique is that following a paper Aghajanyan et al.(2020) which discovered that when pre-trained models are adapted for a specific use case, their weight parameters of a low intrinsic dimension, meaning we can project the weights into a lower dimensional sub space without loosing much accuracy. Smaller matrices, same performance.

Before going further, a quick reminder of how we can view neural net training. During the training of a network, at each step we have the original weights $W$ which we update during back-propagation with the change in weights $\Delta W$ given the new training samples to get the new set of parameters $W´= W + \Delta W$.

Inspired the insight above, the authors hypothesised that this update matrix ($\Delta W$) is also of low rank and be decomposed into 2 much smaller matrices giving, $∆W = BA$ , with $B$ and $A$ having dimensions of $B ∈ R^{d×r} , A ∈ R^{r×k}$. Here $r$ is much smaller than the dimensions of the original matrix and is a parameter chosen to balance accuracy, computation, and memory efficiency.

The great thing about LoRa is that it incurs little or no inference latency, depending on how you serve (more on that in a second). It has shown to have have excellent accuracy from small to large models, so it scales well. In tests on GTP3 it reduced the memory required during training by 3X and the parameter count/checkpoint size by 10,000X when $r$ = 4.

After fine-tuning, we have our separate and decomposed learned update matrix. Now, when it comes to serving, we have a choice. We can add it to the original pre-trained model, which gives us zero additional serving latency, or we keep it separate allowing us to swap out one adaption matrix other fine tuned adaptions. This results in only a small increase in serving latency but gives us maximum flexibility. We can have one base model, a large pre-trained model, and have the option to apply any number of learned adaptions.

Finally, another benefit of this technique (along with many other PEFT techniques) is that LoRA is orthogonal to the other methods, so we can combine for even more gains, eg: combining with prefix tuning and adapters.

Wrap-Up

And there you have it! we’ve explored how off-the-shelf AI models, while powerful, often fall short for specific business needs. Simple methods like zero-shot and few-shot learning have their limitations, especially with complex tasks.

This led us to Model Tuning and Parameter Efficient Fine Tuning (PEFT), innovative techniques that allow us to fine-tune massive models without the high cost and complexity of traditional methods. By updating only a fraction of the parameters, PEFT makes it possible to adapt pre-trained models efficiently and cost-effectively.