The Transformer

- In 2017, Google researchers introduced the Transformer arhitecture for the purpose of translation: Attention Is All You Need

- The paper had a huge impact on AI, not just because it led to impressive results in translation accuracy, but due to the fact that this new architecture did away with recurrence or convolutions, allowing data to be processed as independent from each other, unlocking the way to run calculations in a highly parallel fashion, leveraging modern increases in GPU power.

..the Transformer requires less computation to train and is a much better fit for modern machine learning hardware, speeding up training by up to an order of magnitude.

The Architecture

Overview

The Transformer follows an encoder decoder architecture as first laid in the seminal paper Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder–Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation.

This means that a subnetwork called an encoder, processes the input, transforming it into a fixed length vector that represents the abstract meaning of the sentence or input. This vector is sometimes referred to as a “Thought Vector”. Later this abstract representation is passed to the decoder subnetwork, which converts this abstract “thought” back into concrete words. In the case of the introductory paper it was translating one a phrase in one language to another.

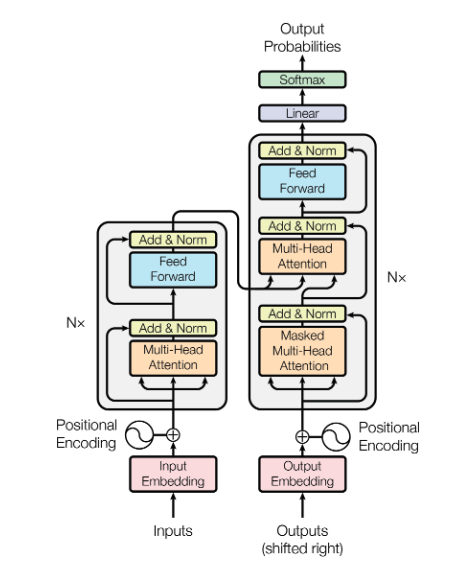

Now back to the Transformer, in the below image below shows how it makes use of encoder blocks (left) and decoder blocks (right). Each encoder block is repeated N times (the original paper uses 6) and consists of a number of sub-components which will dig into . You might be asking yourself what’s happening in each of these encoder blocks and why do we need to stack 6 of them ? Well the main reason for that is to learn hierarchical representations. Just like in a convolutional network, as we apply multiple layers, the model is able to capture increasingly complex and abstract features.

The initial layers might capture simple patterns like individual words and their immediate context, such as recognising the difference between “bank” (where you keep your hard earned money) and “bank” (the banks of a river). As we rise through the layers, the model might start understanding more complex things like phrases and how words depend on each other, such as identifying subjects and objects in sentences. The deeper layers then could grasp even more abstract concepts, such as sentiment (positive or negative), the main topics being discussed, and the relationships between different sentences.

So now that we have broad idea of what the Transformer looks like, let’s dig into the details.

Input: Going from raw text to consumable inputs

So we can’t just feed the machine raw input text, we all know that computers are calculation machines and like to work with numbers, so that’s what we are going to feed it.

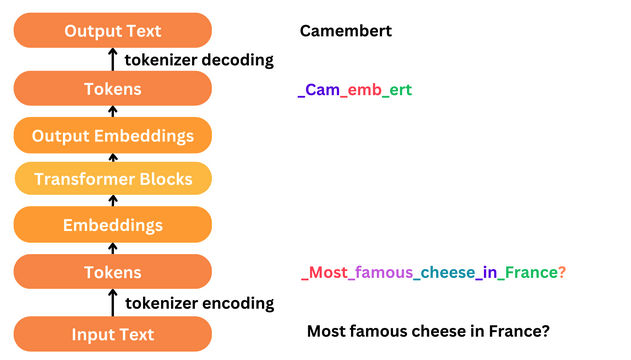

And how do we get from something like “The quick brown fox…” into the final input ? Well it’s a three part process.

- First we need to break raw text into smaller building blocks (sentences, words, characters, etc..) through a process called Tokenisation.

- Then we need to convert our building blocks into numerical representations, called Embeddings.

- Finally, we need to give the Transformer a way to know how words are ordered. Transformers are incredibly fast because they don’t process data sequentially, but in parallel, but this means they don’t inherently understand word order. We use positional encodings to give it some notion of the sequence of words in a text.

Tokenization

As I previously mentioned, we’ll want to take large pieces of text and break them down into smaller blocks. It’s this process of breaking down raw input text to smaller blocks that we call tokenisation, with the resulting blocks known as tokens.

There are many different tokenizers available each with it’s own pros and cons (see this HuggingFace article). See Andrej Karpathy’s Twitter thread for more details on the challenges faced with Tokenizers.

Some things to consider are, the smaller the block the bigger the vocabulary size, which leads to increased model complexity. However this model complexity can be offset by other advantages. e.g: character level tokenisation doesn’t suffer from issues the word level tokenisation does such as new unseen vocabulary.

Input Embeddings

Word embeddings are necessary as we need to give the architecture some machine intelligible data to work with, hence transform words → numerical vectors. So after the tokenisation process we map each token to it’s own vector of fixed length d_model. Usually in these types of models, the vectors are initialised with small random values and the embeddings are updated and learned during the training process.

Positional Encodings

The positional encodings are a tool to give the Transformer some sense of the order of words, as the models attention mechanism doesn’t naturally take the order of words into account like RNNs do.

In the paper the authors used both hand crafted positional encodings and learned ones, with both performing equally well.

Since our model contains no recurrence and no convolution, in order for the model to make use of the order of the sequence, we must inject some information about the relative or absolute position of the tokens in the sequence. To this end, we add “positional encodings” to the input embeddings at the bottoms of the encoder and decoder stacks. The positional encodings have the same dimension d_model as the embeddings, so that the two can be summed.

Putting It All Together

Once we have the positional embeddings, we sum the positional embeddings with the input embeddings to get our final input values for the encoder and decoder blocks. So here’s a review of the full process.

- Text Input: “The quick brown fox”

- Tokenization: [“The”, “quick”, “brown”, “fox”]

- Embedding Layer:

- Token Embeddings: [E(“The”), E(“quick”), E(“bown”), E(“fox”)]

- “The” → [0.3, -0.1, 0.2, …] (randomly initialized vector)

- “quick” → [0.5, 0.2, -0.3, …] (randomly initialized vector)

- “brown” → [-0.6, 0.7, 0.4, …] (randomly initialized vector)

- “fox” → [0.2, -0.3, 0.6, …] (randomly initialized vector)

- Positional Encodings: [P(1), P(2), P(3), P(4), P(5), P(6)]

- Combined Embeddings: [E(“The”) + P(1), E(“quick”) + P(2), …, E(“fox”) + P(4)]

- Token Embeddings: [E(“The”), E(“quick”), E(“bown”), E(“fox”)]

Review and Recap of Part 1

That’s it for now, we’ve got a brief overview of why the Transform architecture was so impactful, how and why it’s organised into stacks of encoder and decoder blocks, and how we go from raw data into something consumable by the system.

In the next blog post we’ll take a deep dive into the encoder & decoder blocks and how the attention mechanism works.

Resources

- Original Paper: Attention Is All You Need

- Blog Post: The Illustrated Transformer