If you missed the start of this series please check it out from that start, A Guide to LLM Inference (Part 1): Foundations

Attention Optimisation Strategies

Now that we have some background on how LLMs process each request, from the memory requirements, bottlenecks and caching strategies, let’s dig into how we can optimise the attention mechanism of the Transformer.

PagedAttention (Paper)

PagedAttention was introduced to tackle memory managed in high throughput environments when serving LLMs. Before introducing PagedAttention, systems struggled to efficiently manage memory as the KV cache is massive and it grows and shrinks during inference (as tokens are generated and requests are finished). Given this inefficient management, it lead to waste in the form of memory fragmentation and duplication.

The main issue with how the KV memory was managed, is that for a request, values are stored in contiguous memory space (memory blocks having consecutive addresses). This is inefficient when the memory used can grow and shrink over time and the duration required and length of memory is not known up front (until the generation has finished).

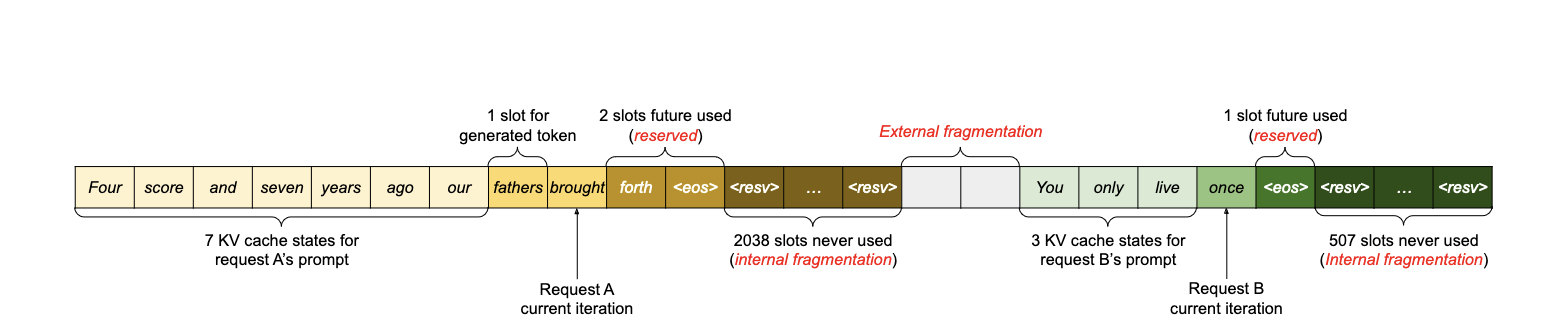

Naive memory management led to fragmentation (internal & external) and duplication of some KV values:

- Internal fragmentation happens when memory is allocated in blocks of fixed sizes, and the memory that is actually used is smaller (sometimes significantly) than the requested memory.

- External fragmentation occurs when free memory is scattered in small blocks throughout the system, and even though there is enough total free memory, it is not contiguous, and thus cannot be allocated to processes that require larger contiguous blocks of memory.

In the example shown above, a request, gets pre-allocated a contiguous chunk of memory using the requests maximum length (e.g Request A 2048 tokens), but only uses 11 tokens. This leads to internal fragmentation, as the generated sequences is much shorter and doesn’t make use of the extra reserved memory. And when requests have different lengths (like Request B), repeated allocation eventually leads to external fragmentation of physical memory, mean it can’t be used for anything.

Im summary we have unused memory allocated to requests that can’t be used for new requests, and a lot of memory address between chunks allocation to other requests aren’t large enough to be used by new requests. In fact, the authors of the paper showed that only roughly 20-38% of the memory assigned for KV cache actually contains a token.

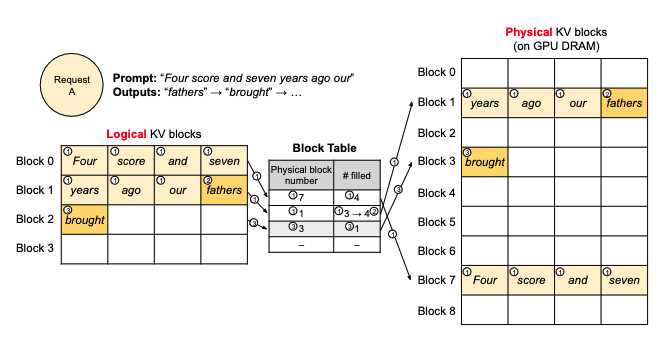

In PageAttention, we instead assign blocks of memory in a non contiguous way that’s done on demand. It eliminates external fragmentation, as all blocks have the same size. And provisioning blocks on demand greatly reduces internal fragmentation as almost everything requested is used. Finally it avoids duplication when using some parallel decoding strategies by allowing memory sharing between alternative decodings. We explore these decoding strategies in this post, but see the paper or this HuggingFace article for more.

To enable this, the authors introduce a KV Cache Manager that partitions the memory into fixed-size pages (blocks) and maps requests KVs to those blocks. In this system each request is represented by a series of logical (virtual) KV blocks. Then a KV block manager maintains block tables, that maps requests to physical KV blocks in memory.

In the image below we can see 2 requests that have overlapping blocks of memory, which are being allocated on demand, so no internal fragmentation, and with even block sizes are, either request or even a third request could consume any intermediate memory blocks, reducing external fragmentation.

FlashAttention (Paper)

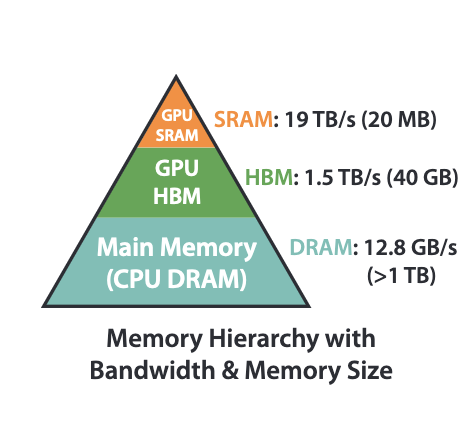

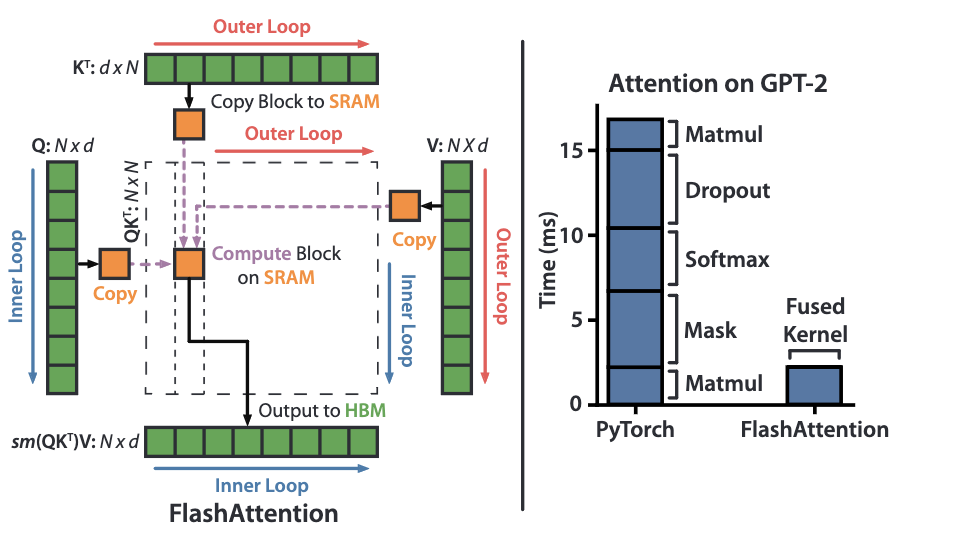

FlashAttention is an exact method to improve the efficiency of the attention calculation by reducing memory read / writes and without the need store intermediate results in memory. It does this by “fusing” (grouping) operations into one step, and taking advantage of a GPUs higher speed SRAM (which is an order of magnitude fast than HBM). As we’ve said before, transformers are largely memory bound so any improvements we have make in reducing the memory footprint will greatly increase efficiency.

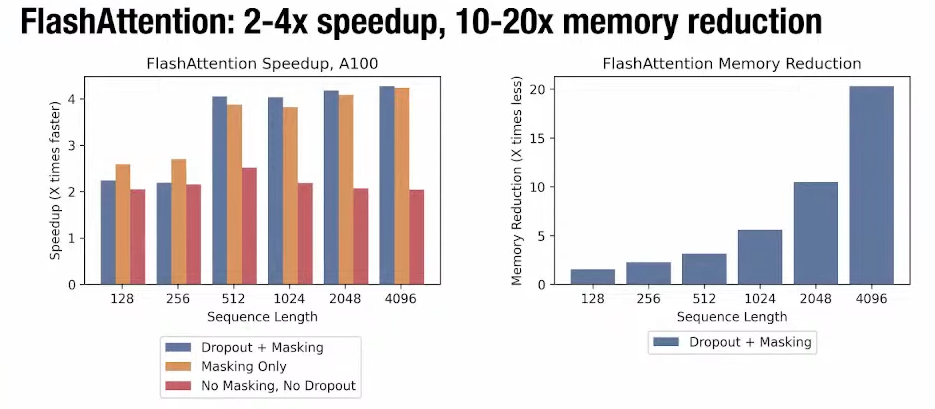

FlashAttention exploits the asymmetric GPU memory hierarchy to bring significant memory saving (linear instead of quadratic) and runtime speedup (2-4× compared to optimized baselines), with no approximation.

Standard Attention is implemented as follows: Given the input sequences of $Q, K, V$, we want to compute the attention output $O$:

- $S=QK^T$

- $P = softmax(S)$

- $O = PV$

The normal implementation stores the intermediate matrices $S$ and $P$ to HBM which requires $O(N^2)$ memory.

FlashAttention has 2 innovations that lead to speed advantages:

Tiling: This involves breaking the matmul operations into blocks.

- We load the sub blocks of $Q, K, V$ from slow HBM into fast SRAM.

- We calculate partial attention scores $QK^T$

- We apply the softmax to this blocked operation. Take note here, we are now trying to calculate the softmax over a sample of the full $QK^T$, a normalising function that usually requires the full matrix. The paper finds a way to make this partial softmax calculation work by keeping track of some extra statistics and scaling the outputs of each of the blocks.

- We multiply the $partial\_softmax(QK^T)$ by $V$ to get a partial output $O_i$

- Once all blocks have been processed, the partial results are combined in HBM to form the final output matrix $O$.

Recomputation: Instead of storing intermediate values required for the backward pass in memory, recompute them on the fly. The paper explain it very clearly:

The backward pass typically requires the matrices $S$ and $P$ to compute the gradients with respect to $Q$, $K$, and $V$. However, by storing the output $O$ and the softmax normalisation statistics, we can easily recompute the attention matrices $S$ and $P$ during the backward pass from blocks of $Q$, $K$, and $V$ in SRAM.

The efficiency gains of FlashAttention are very impressive. Speeding up the calculation by 2-4x and reducing memory between 10-20x. This has also enabled larger context windows.

Since introducing FlashAttention in 2022, the authors have since iterated on the original design in a follow up paper: FlashAttention-2: Faster Attention with Better Parallelism and Work Partitioning, which provides a 2x speedup compared to the original implementation!

End of Part 2

So we’ve explored two innovative strategies for optimizing attention in LLMs:

- PagedAttention: This technique significantly improves memory management, reducing fragmentation and enabling more efficient use of GPU memory during inference.

- FlashAttention: This method revolutionizes attention calculation by minimizing memory operations and leveraging faster GPU memory. It employs smart tiling and recomputation techniques for impressive performance gains.

These approaches represent major advancements in LLM efficiency, enabling faster processing and support for larger context windows. As the field progresses, we can anticipate further innovations that will continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible with large language models.

If you missed the start of this series please check it out from that start, A Guide to LLM Inference (Part 1): Foundations